Review:

Harper Lee specialist Dean Thomas DiPiero reviews the long-awaited follow-up to "To Kill a Mockingbird."

By Thomas DiPiero

It’s strange to think of Scout, eternally a 10-year-old desperado, as an adult. Strange to think that Jem is dead. Strange to think that “Go Set a Watchman,” the original draft of the book that became the classic “To Kill a Mockingbird,” exists at all.

Thomas DiPiero |

And most of all, it’s strange to read that Atticus Finch, the moral compass and hero of “Mockingbird,” is a racist.

“Boycott the book!” some commentators cry. Should have never been published, other critics say.

But to me, Atticus’ complexity makes “Go Set a Watchman” worth reading. “Mockingbird” was written through the eyes of a child. “Watchman” is the voice of a clear-eyed adult.With more than 40 million copies in print, “Mockingbird” is an international sensation. Most of us read it for the first time in junior high or high school, likely at too young an age to understand fully its brilliant handling of the complex issues of racism, sexual violence, abuse, drug addiction and murder.

Much of Lee’s genius lies in her ability to depict these serious and intricate components of American life in ways that seem simple.

Atticus repeatedly tells his children to walk in others’ shoes, to try to view the world from inside others’ skins. As adults, we recognize that trying to understand others’ perspectives is a lofty and socially useful goal. But we also see that presuming we can empathize with people whose histories and life experiences are completely different from our own can be a potentially dangerous enterprise, one leading not only to misunderstanding, but also, possibly, to death.

Even the work’s principle metaphor — that of the mockingbird, which imitates the songs of other birds — reminds us that there are some among us whose voices are not heard, or not allowed to be heard.

“Watchman” is more internal. The title comes from the Book of Isaiah: “For thus hath the Lord said unto me / Go, set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth.”

Every man’s watchman, a character says in the book, is his own conscience.

The first chapter, released Friday, shows us that the adult Jean Louise Finch, aka Scout, has refined the characteristics we associate with her as a girl. She still dresses in gender-neutral attire, and she remains somewhat incorrigible, fiercely independent and sharply critical. . .

With “Mockingbird,” Harper Lee made us question what we know and who we think we are. “Go Set a Watchman” continues in this noble literary tradition.

Prof. DiPiero talks about "Go Set a Watchman"

Prof. DiPiero talks about "To Kill a Mockingbird"

TKAM: Lost in Translation for Kids?

Maybe So, Says SMU Expert

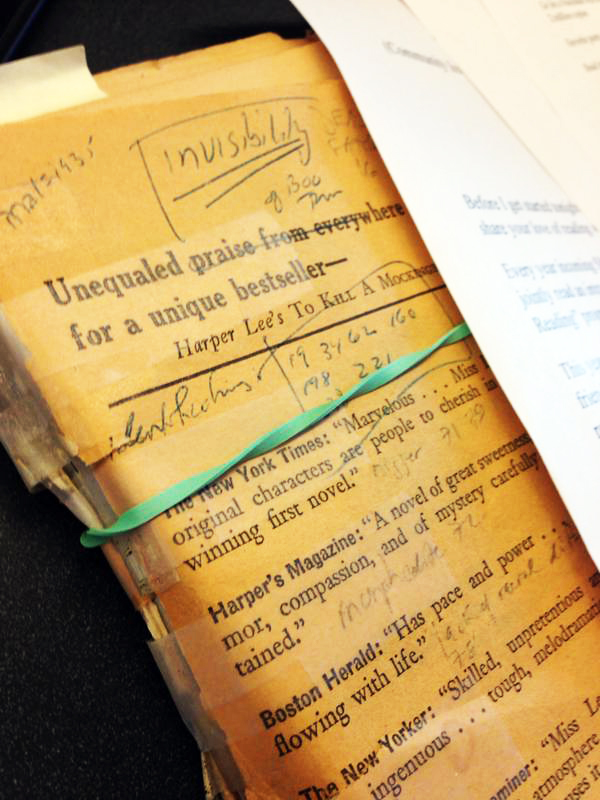

SMU Dedman College Dean Thomas DiPiero discussed Lee’s masterful To Kill a Mockingbird at a SMU Community Outreach-University Park Public Library event June 18. Here are a few highlights from his talk:

- As a scholar of French literature, DiPiero has read the novel in French, where it goes by the title Ne Tirez Pas Sur L'oiseau Moqueur, which translates to “Do Not Shoot at the Mockingbird” and “misses the whole point,” DiPiero says. The book’s overall translation “catches the tone” of the original, but left him wondering, “Can you understand this novel if you’re not American? I don’t think you can. I think you have to understand what life is like in a small town in the South, even if you never lived there. You have to understand American racial politics. You have to understand something about violence in the South during the book’s time.”

- Despite TKAM being widely read by high-schoolers and junior high-schoolers, “it ain’t kids’ stuff,” DiPiero says. Many of the novel’s complexities aren’t easy for young minds to grasp. “I mean, it’s a pretty difficult novel. It’s about rape. Incest. Child abuse. Drug addiction,” he explains. “And the message we’re encouraged to come away with at the end is, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we can all just get along and see things from others’ perspectives?’ The truth is, it’s much more complicated than that.”

- DiPiero suggests adults read the book for a richer understanding of its racial and cultural complexities. He first read TKAM in ninth grade, but after re-reading it in his 30s, he was gobsmacked by what he missed in the book the first go-around — in particular “gothic” elements of ambiguity – the indefinable “in-between things” in life, the murky gray areas of morality and “norms” seen through a perverse lens.

- As for the book’s title, “What do we know about a mockingbird? It doesn’t have a call of its own. It only imitates other calls,” DiPiero says. “That describes a lot of the characters in the book who aren’t in powerful positions. They have to learn to speak through, or with, another language.”

# # #