SMU palaeobotanist Bonnie Jacobs spent 15 years studying ancient plants to help predict future climate change

Palaeobotanist Bonnie Jacobs has spent 15 years studying ancient plants to help predict future climate change.

By Kenny Ryan

SMU News

Bonnie Jacobs |

DALLAS (SMU) – In the movies, the adventure begins when the sinister industrialist abducts Harrison Ford to plan a hunt for lost treasure.

For Bonnie Jacobs, it started with a phone ring.

In the late summer of 2000, the SMU palaeobotanist was working in her office on the third floor of the University’s Heroy Science Hall when an old colleague called with exciting news about Ethiopia. He’d just returned from a dig site where he’d expected to find fossils from eight million years ago. Instead, he’d found fossils from 27 million years ago – mostly plants. He thought it was a job for Jacobs, one of the premier palaeobotanists of African flora.

Although Jacobs had just recently returned from field research in Tanzania, “There is something about Africa that keeps people coming back again and again,” she says. “Much of tropical Africa’s ancient plant history was a mystery, so that’s what attracted me. Not just the romance of exploration, but also because so little was known.”

Africa called, Jacobs answered, and a 15-year adventure in Ethiopia was born.

FIFTEEN YEARS

Bonnie Jacobs’ expedition gathers for a group picture near its Mush Valley campsite in 2011. Jacobs is fifth from the left in the second row. |

Fifteen years is a long time to dedicate to a project.

It’s 15 dry winters of digging in 90-degree heat in the day with occasional frosty mornings, and 15 rainy summers of research in a museum. It’s 15 years of making close friends. And it’s a long time to get to know a place and then have to say goodbye.

This summer, Jacobs made the final trip at the end of her latest grant.

“I’ve asked myself lately, is it really the end?” Jacobs says. “When you’re there, you’re doing what you love to do with great friends as company. When I was in the field, I was in the field with colleagues I’d become friends with over years.”

The cast of friends was old and new. There were American researchers and graduate students – a half-dozen of whom would earn their advanced degrees during the project. There were local Ethiopians like Mesfin the driver, Uncle Alemu the elder statesman-like lawyer who became a friend, and Achamu the cook, who baked fresh bread and cakes in an oven he buried in the earth.

One day, Achamu even made donuts, and home suddenly didn’t seem so far away.

Jacobs came to think of Ethiopia as a second home, and the researchers and locals became a second family. The graduate students were like children Jacobs was helping to launch from the roost.

“I can already think right now of reasons I have to go back,” Jacobs said.

CAMP LIFE

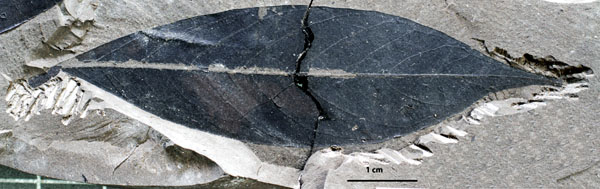

This 22-million-year-old legume fossil was collected by Bonnie Jacobs’ expedition from Mush Valley in 2011. |

The first challenge of traveling to Ethiopia is fitting all of the necessary dig equipment into a 50-pound suitcase at DFW airport – and dealing with the baggage fee that makes no exception for important paleontology.

Once in the air, it’s roughly a 10-hour flight to Europe and then another 10-hour flight to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, where even the most resilient team needs hotel down-time to adjust to the nine-hour time difference.

Each expedition, typically numbering a half-dozen scientists and a half-dozen locals, such as Mesfin, Achamu and government or museum officials, would then drive a pair of Land Cruisers into the Ethiopian highlands, where a knee-high wheat called teff is harvested from the rocky earth.

It was not uncommon for some Ethiopian university students to make the trip from the city to contribute, as well.

Jacobs dug at two sites during her time in Ethiopia: Chilga, in Ethiopia’s northwest, and Mush Valley, closer to the center. At either site, Achamu’s kitchen tent was always the largest one. During the first trips, satellite phones were used to communicate with the rest of the world, but in later years, cell phones became ubiquitous.

Chilga and Mush Valley were similar sites, where windy roads stretched over sparsely-vegetated hills split by narrow ravines and dotted by scattered trees. Fields of yellow teff were everywhere. Temperatures rose to the 90s by day, which felt hotter than that under a baking sun, and dropped to the 50s by night. Jacobs always packed a fleece.

The night sky at camp was a revelation, the stars stretching to the infinite.

Long ago, both sites had been a rainforest. The evidence hides in the rocks. This is what Jacobs spent 15 years digging for.

DISCOVERY

Jacobs will tell you that most discoveries are made after long days of searching, digging and sweating, but one of the most prized discoveries from her first trip to Ethiopia was the result of a sideways glance.

“We went to a place with volcanic ash and, because this ash was eroding out at the surface, you could just walk up to it and look down and see these huge palm frond impressions there,” Jacobs recalls. “Right next to them were these fossilized legumes (peas and beans are legumes). I’d never seen those two plants together in a fossil community sample before.”

When a discovery like this is made, one that challenges preconceived notions and expectations, there is no, “I don’t believe this,” moment for Jacobs.

“I see it, I have to believe it and I need to learn more about what this means,” Jacobs said.

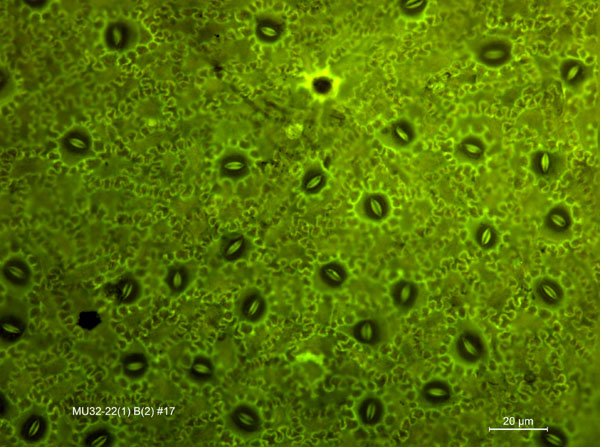

Many of the fossils discovered at Chilga, and especially Mush, are so finely preserved they can be studied under the microscope as easily as if they were living plants. Jacobs can count the stomata — tiny openings plants use to “breathe” — to measure how much CO2 was in the air when the fossilized plant lived. More CO2 in the air means fewer stomata were needed, and vice versa.

Jacobs can also judge how much rain fell, on average, during a particular year and how long the dry season lasted from the types of plants she discovers and the size of their leaves. Isotope research by her SMU colleague, Neil J. Tabor, a professor of sedimentology, can reveal what the temperature was like when the plants lived, as well.

This years-long research paints a picture of how the world’s climate changed in the past, which helps scientists today test climate-change models they use to predict the future.

If, after taking into account all the known variables of the climate 27 million years ago, a model can correctly predict what the climate looked like five million years later, Jacobs says it’s a pretty good model.

Jacobs’ research also helps paint the picture of what happened when the land masses of Africa and Eurasia merged roughly 24 million years ago — right between the time periods revealed by fossils at the Chilga and Mush Valley dig sites, which date to 27 and 22 million years ago, respectively. Jacobs and her colleagues can see which animals and plants won the evolutionary battles that must have occurred once life on the formerly isolated African continent was suddenly thrown into direct competition with immigrants from Eurasia.

That period of competition took place when true carnivores like leopards, lions and other cats first entered Africa, and when once-dominant creatures like the arsinoithere (imagine a cross between an elephant and a rhino, with a massive horn over each eye) died out. The big cats replaced other archaic meat-eaters known as the creodonts.

It’s when Africa became the kind of dangerous place we think of it as today.

HAZARDS

This 22-million-year-old frog fossil was collected by Bonnie Jacobs’ expedition from Mush Valley in 2010. |

Typhus, yellow fever, typhoid and meningitis are all concerns when working in Africa, but Jacobs always inoculates herself against those diseases months before embarking on an expedition.

Ebola never threatened Ethiopia, for which Jacobs’ team has been thankful. Violence was never a risk in the highlands, either, so the team rarely needed guards.

The real threat usually came from what crawled in the dirt and mud the team shared like a common skin.

Jacobs recalls waking to sounds of a great commotion one winter night: One of the Ph.D. students who’d accompanied the expedition was throwing his belongings to and fro in his tent, which was crawling with ants.

The ants were harmless, but he didn’t know that. Cursing ensued.

Then there was the summer when sand fleas overran the camp – and that was definitely more harmful. African sand fleas aren’t the same as American sand fleas. In Africa, they are critters that burrow into the skin, where they lay eggs that will hatch into larva that eat their way out if not removed. Jacobs recalls her own close encounter with a burrowing flea.

“I dug it out with a needle,” Jacobs says. “You have to squeeze out the egg mass, which is this giant, white pus-like thing, and get the flea out. It was so cool!”

Jacobs was lucky. She had only one sand flea that summer. Colleagues who wore sandals around the camp had as many as a dozen on each foot.

WRITING

Mush Valley, seen here in 2010, was located in the Ethiopian highlands near the heart of the country. |

After 15 years of visiting Ethiopia, Jacobs’ grant is nearing its end. She’s now back in her office on the third floor of Heroy Hall, not far from where she got the phone call that started the adventure so many years ago. Her days are spent writing reports about the discoveries her team made and preparing for a fall semester of Intro to Environmental Science students.

The research will be completed after more computing and writing, and the end is getting close. In November, Jacobs will present her findings to the Geological Society of America during its meetings in Baltimore.

Next, Bonnie will turn her attention to the environmental history of the Dallas area’s Trinity River waterway, but she doesn’t think she’s seen the last of Africa just yet.

“I have, in my mind, always this thought that I will go back,” Jacobs said. “People who work in Africa always go back.”

###

21297-nr-8/26/15-kr