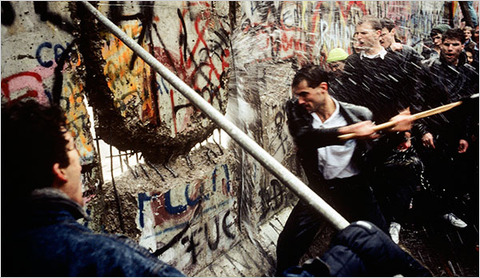

Toppling the Berlin Wall, 25 years later: A legacy in dispute

What brought down the Berlin Wall 25 years ago this week is still in dispute, says SMU historian Jeffrey Engel.

By Jeffrey A. Engel

Jeffrey A. Engel on CNN" President Ronald Reagan's famous "Berlin Wall" speech. |

The Berlin Wall continues to haunt the world. Only shards remain of the concrete and barbed wire that once divided a city and split a continent. Few can be found in Berlin itself. Sections adorn a men's room in Las Vegas, a pedestrian mall in South Africa and the dining room at Microsoft. Bits can even be found on EBay (buyer beware).

But the wall's legacy, not its collectibility, is the problem. The world cannot agree on precisely why it fell, and more broadly why European communism collapsed and the Cold War ended. Four contradictory explanations dominate, from the most powerful corners of the Earth: the United States, Russia, Europe and China. This is no mere academic debate. How political elites understand the past directly affects their strategies for the future, and conflicting readings of a shared pivot point offer a recipe for ongoing international instability.

Americans largely understand the Cold War's end as a story of triumph. "By the grace of God," George H.W. Bush declared, "America won." Forty-plus years of economic and military dominance won, to be specific. After decades of containment, Ronald Reagan commanded "tear down this wall," and the Kremlin, recognizing the folly of continuing an exceedingly expensive and unwinnable arms race, complied (a few years later, but still).

Soviet surrender, coupled with a democratic eruption in Eastern Europe, symbolized to American minds acceptance of not just U.S. global dominance, but of American values. Europe's oppressed peoples wanted to be like us, American leaders thought, because as George H.W. Bush said, "We know what works. Freedom works." All but ignoring the activism that helped erode communism from within, and lumping together Eastern Europe's reforming and recalcitrant regimes, the American story offered a profoundly simple, yet profoundly powerful explanation for the Cold War's end: Might makes right, and we were right all along.

Like all dominant historical narratives, this one's accuracy matters less than its popularity, even as it offers an obvious recipe for subsequent success: So long as the U.S. is strong enough to withstand any threat while holding fast to its ideals, the world will eventually fall in line. Believing ourselves capable of outspending and outfighting any potential adversary, just as during the Cold War we might time and again liberate oppressed peoples who yearn only for the opportunity to enjoy our way of life.

"If the wars of the 20th century … have taught us anything," Bill Clinton explained, "it is that we achieve our aims by defending our values and leading the forces of freedom."

Such triumphalism proved bipartisan. "The toppling of Saddam Hussein's statue in Baghdad," George W. Bush declared in 2003, "will be recorded alongside the fall of the Berlin Wall as one of the great moments in the history of liberty." Five years later, Barack Obama situated his international coming-out party in Berlin. In the midst of financial crisis and international critique, the site offered a reminder that the American system had worked. "Let us remember this history, and answer our destiny," Obama preached, "and remake the world once again."

A plaque marking where the Berlin Wall once stood. |

Europeans don't buy this story. Their prevailing explanation for communism's collapse gives credit not to American might and ideals, but instead to their own continental elan. Force had not destroyed communism. Instead, its absence made Eastern Europe's velvet revolutions possible. By avoiding war for more than two generations, a long time given recent history, sage European strategists gave communists time to come to their senses.

Peace was no accident in this European narrative. It derived from transnational institutions and integration designed to heal bloody divisions. Europe had nearly committed suicide in World War I. It tried again in World War II. No one believed it might survive a third try in the Atomic Age. So its leaders finally forged a common home, melding divergent economies, religions, cultures and nations into a society in which even the threat of force had no place. By the close of the 1980s, victory seemed at hand. "The watchword of post-1945 politics: ‘We must never go to war with each other again,’" the president of the European Commission explained, "buoyed the hopes of those who built the community. That objective has been achieved."

Europe had vanquished war! The hubris underlying that conclusion exceeds even the belief that people the world over desired to be American. Yet this narrative explained not only Europe's success, but also communism's surrender. When Mikhail Gorbachev spoke of a "common European home," stretching "from the Atlantic to the Urals," he was, it seemed, expressing less a desire to control Europe than to marry it, and a willingness to forsake even socialism to fuse East and West.

Europe's ongoing fascination with consensus reveals in large measure why its leaders have been so critical of aggressive U.S. policies over the last two decades. Force is inherently destructive, the post-1945 generations believed, at best a temporary fix. So long as we don't force others to see the virtues of our society, onetime enemies will eventually tear down their own walls in order to join us. They already had.

Russians typically draw more bitter lessons from 1989. Gorbachev's hopes for further integration with Europe were soon dashed. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization expanded, despite what Moscow took to be explicit promises that it would be held at a newly unified Germany's eastern border. The European Union barred its doors. Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and Hungarians, liberated from Nazi tyranny at great cost and supported by the Kremlin for decades, turned westward without even looking back.

A demonstrator armed with a hammer pounds at the Berlin Wall next to the Brandenburg Gate on Nov. 11, 1989. (Photo courtesy of The New York Times.) |

And there was no second Marshall Plan. This time, the victors merely left their enemies to rot. The post-Soviet economy collapsed. Food supplies plummeted. Life expectancy rates declined while alcoholism and infant mortality soared. Humiliation followed hunger. Russians saw the United States flex its military muscle in the Balkans, Afghanistan and the Middle East, even as Moscow's interventions in Chechnya, Georgia and Ukraine produced scorn. The people whose strength had once made the West shake with fear were now chastised for seeking order in their own backyard by a rival willing to send troops halfway around the world at the slightest provocation.

Vladimir Putin in particular views 1989 in tragic terms. The Soviet collapse was "the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century," he concluded. His lesson: Western promises are worthless. Russia is only respected when feared. He dared not compete with the United States militarily, but instead found common cause with other states that consider America arrogant and hegemonic, while employing the tools at his disposal — including energy resources, cyber proficiency and a United Nations Security Council veto — in pursuit of narrow nationalistic interests. Let the Europeans talk and the Americans bluster, Putin reasoned. He acts.

China's legacy of 1989 is the most inwardly focused of the four, as the year conjures memories not of Berlin, but instead of Tiananmen Square. Eastern Europe's upheaval worried Chinese leaders, haunted by their violent Cultural Revolution when crowds went awry. "Every effort should be made to prevent changes in Eastern Europe from influencing China's internal development," Communist Party officials declared in March 1989. In April, demonstrators were grudgingly tolerated. By May, they were confronted with batons and tear gas. June brought tanks and machine guns.

Among the regimes that faced demonstrations in 1989, only China's government remains in power today. Why? Because it showed no mercy. East German officials lacked the stomach to fire on protesters. So too the communist hard-liners in Moscow whose 1991 coup brought masses into the streets. Deng Xiaoping was not so bothered. "You carry these things out," he said, "and the Westerners forget."

Yet China's leaders also recognized that they ignored the demands for a better life at their peril. The government made an implicit deal with its citizens: political sclerosis in exchange for economic growth. Woe be it to whoever in Beijing fails to keep the good times rolling.

The overall lesson of 1989 is not an optimistic one. Each of these great powers barrels ahead guided by its own version of the past. Europe remains committed to collectivism, standing up to geopolitical bullies with only the greatest reluctance. The United States remains committed to fielding the world's most powerful military, even at the cost of its economic base and the educational system that generated such power in the first place. Russians are consuming neighbors as if striving to win the 19th century anew, no matter the sanctions. And the Chinese continue to crush dissent, even as they manipulate their yuan and order unnecessary projects to ensure employment, waving the bloody shirt of nationalism whenever domestic support seems to sway.

Collisions are only a matter of time when conflicting lessons of history prevail. Anxious Americans might trigger a new arms race with China. That strategy worked against the Soviets. Europeans might put such faith in conciliation that they fail to see a true threat at their door. They've done so before. Putin and his successors might one day step too far, triggering real conflict while exacerbating domestic unrest by trading the remnants of prosperity for old-fashioned hard power. Mobs already gather in Hong Kong and might yet roil the mainland if growth declines and the Internet's reach expands interest in the liberties enjoyed outside China's borders.

The new world after 1989 seemed so promising. As the British rock band Jesus Jones explained, watching the wall fall was like "watching the world wake up from history." Because the story of the Berlin Wall's fall reads differently around the world, however, history might yet, alas, have the last laugh.

# # #

More about Jeffrey A. Engel

Jeffrey A. Engel also is an associate professor of history at SMU, a senior fellow at SMU's John Goodwin Tower Center for Political Studies, winner of the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations Bernath Lecture Prize for 2012, and author of the forthcoming When the World Seemed New: George H.W. Bush and the Surprisingly Peaceful End of the Cold War.

Other books he has authored or edited include Into the Desert: Reflections on the Gulf War (Oxford University Press, 2012); The China Diary of George H.W. Bush: The Making of a Global President (Princeton University Press, 2008); Local Consequences of the Global Cold War (Stanford University Press and Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2008); Cold War at 30,000 Feet: The Anglo-American Fight for Aviation Supremacy (Harvard University Press, 2007); and Rethinking Leadership and "Whole of Government" National Security Reform: Problems, Progress, and Prospect (Military Bookshop, 2010).